Why are Music Notes Named the Way They Are?

Most English-speaking countries use letters from the Latin Alphabet (A-B-C-D-E-F-G) to represent musical notes. Between these 7 letter notes are 5 semitone (half step) notes, which are represented by a letter name plus a sharp sign or flat sign.

This gives us 12 unique musical notes. These repeat every octave, and each repeat note name (every A, every B, etc.) sounds like a higher or lower version of itself.

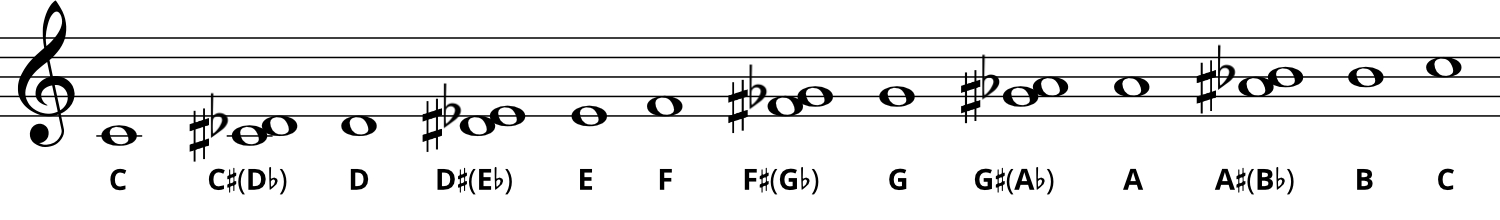

Here are the names of all 12 music notes:

1. A

2. A-sharp (also called B-flat)*

3. B

4. C

5. C-sharp (also called D-flat)*

6. D

7. D-sharp (also called E-flat)*

8. E

9. F

10. F-sharp (also called G-flat)*

11. G

12. G-sharp (also called A-flat)*

* In equal temperament tuning (used worldwide since the 18th and 19th centuries), these notes with two names sound identical; only their name and on-staff appearance differ.

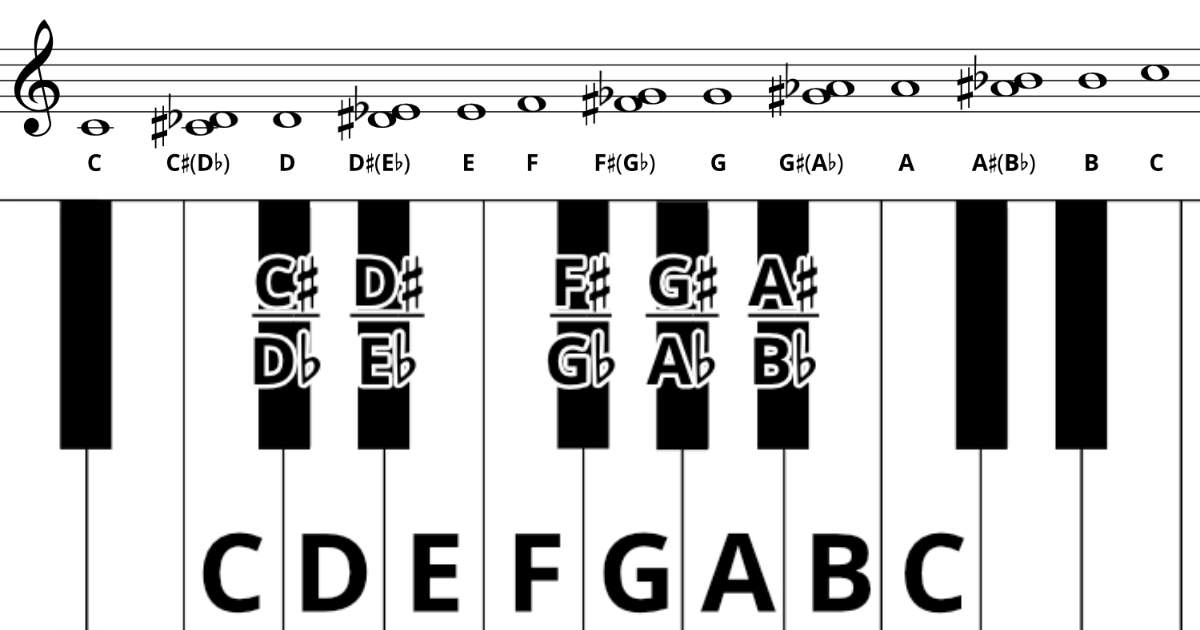

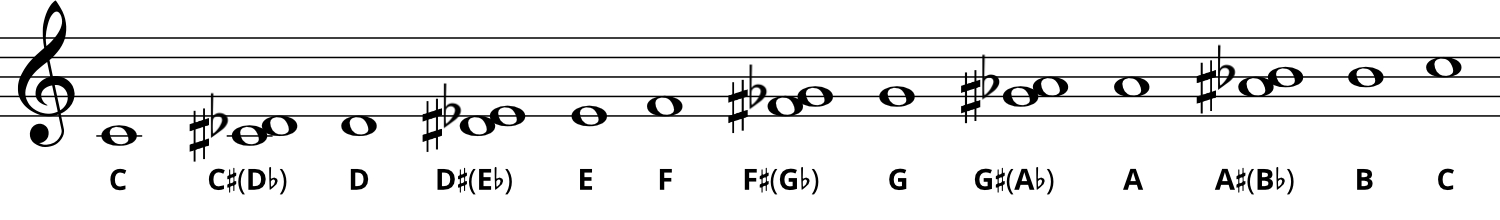

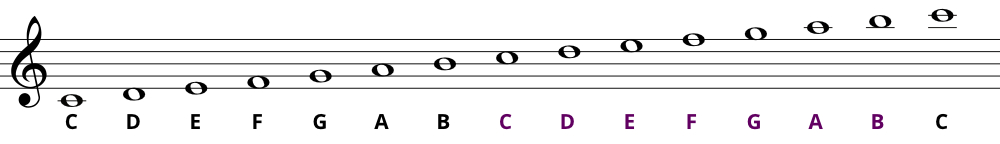

Here are the 12 notes as they appear on the Treble Staff (starting with Middle C). The higher C shows the octave.

The 5 semitones (shown here as double notes with their second name in parenthesis) are enharmonic. This means that for each pair of double notes, the two notes sound the same, but they have a different name and appearance. From the image above, C-sharp and D-flat sound the same, but they have different names and look different on the staff. Which name and appearance they are given depends on which scale or interval is being used at the time.

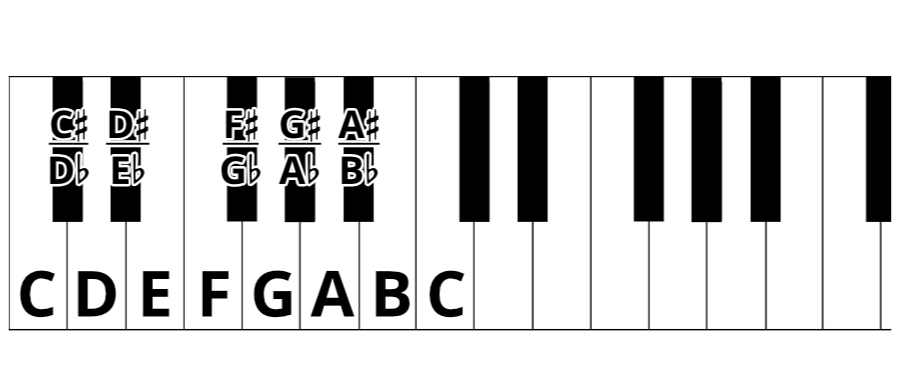

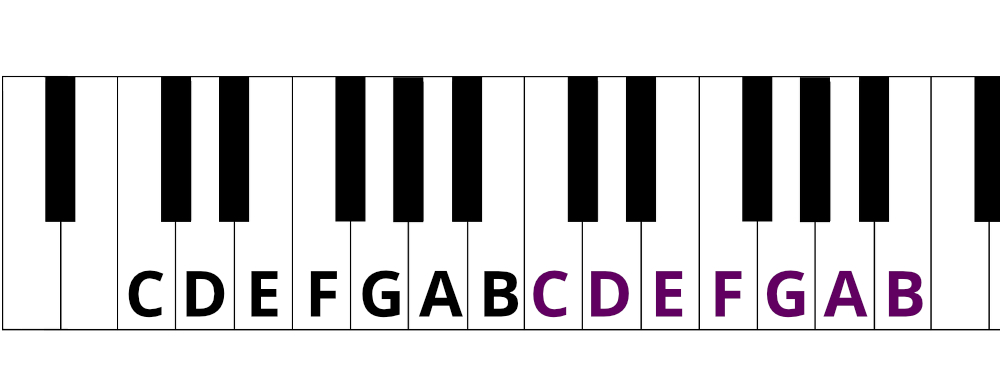

Here are the 12 notes as they appear on the piano. The 7 natural letter notes are represented by the white keys, and the 5 in-between notes are represented by the black keys. The black keys are shown here with both names, and the higher C shows the octave.

What About Solfège Note Names?

Depending on where you live and what language you speak, you may not use the letters A-B-C-D-E-F-G to name music notes. Several European countries (such as Germany) also use letter names, but the natural letter B is replaced by H (A-H-C-D-E-F-G). But many other countries (such as France, Italy, and many Latin American and Arabic-speaking countries) use an entirely different naming system called tonic sol-fa, or solfège (do-re-mi-fa-sol-la-si).

About solfège: Around the year 1000, an Italian named Guido d'Arezzo was credited with naming music notes as shortened syllables from Latin terms. In his system called tonic sol-fa (or solfège), the basic notes of the scale were named Ut-Re-Mi-Fa-Sol-La-Si (Ut was later changed to Do). This note naming system made it easy to remember and preserve music, and today it is still dominant in many parts of the world. (It is also the inspiration behind the song "Do Re Mi" from the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical "The Sound of Music.")

Solfège and letter names are both excellent note naming systems, but since I'm a native English-speaking musician, here I will focus on the letter note naming system most commonly used in English-speaking countries.

Music Notes Are Named After Letters

With the Latin alphabet letter system, music notes are named after alphabet letters. The letters of the alphabet are a conveniently simple way to name music notes. If you know your ABCs, you know the names of the music notes because they're just the first 7 letters of the alphabet, repeated every octave.

Here are the 7 letter note names on the Treble staff. Two octaves are shown to demonstrate that each new octave is a repeat of the first. All notes with the same name sound like higher or lower versions of each other.

Here are the 7 letter note names on the Piano white keys. Just like on the staff, two octaves are shown to demonstrate that each new octave is a repeat of the first. All keys with the same name sound like higher or lower versions of each other.

Why Are Music Notes Named After Letters?

Around the year 500, a Roman named Boethius was credited with first assigning letters of the alphabet to note names. He labeled the lowest tone "A" and named each ascending note the next letter of the alphabet. It was a brilliantly simple naming system; however, part of the reason it worked so well was that in his day, they used only a 2-octave note range to make music (for reference, today's pianos have a range of more than 7 octaves!).

As more instruments were invented, the range of usable notes widened, and more octaves were added over time. This lead to issues with Boethius's note naming system. One issue was that it became too difficult to remember where the octaves were (was an octave above A an H or an O?). Eventually, there were so many notes to name that it became impractical to try to keep track of them all.

So the letter note naming system was eventually simplified to just the 7-note scale (with one letter per scale tone), with these names repeating every octave. This made it much easier to remember all the note names and match pitch in different octaves.

Side note: An even more specific note-naming system (Scientific Pitch Notation) was later developed to label not only each pitch by name, but also by the octave it is in. Learn more about Scientific Pitch Notation here.

Why Are There 12 Music Notes in Music, But Only 7 Letter Names?

We have 12 notes in music, but only 7 have letter names. The remaining 5 notes are given the nearest letter name plus a sharp or flat sign. Here's how this came to be:

The 7 notes with letter names (A-B-C-D-E-F-G) come from the diatonic scale (the most common form of musical scale). The diatonic scale was built thousands of years ago based on harmonious intervals (distances between pitches), mathematical ratios, and what listeners like to hear. Every major scale, minor scale, and modern musical mode (dorian, lydian, etc.) is a type of diatonic scale, and since most music today is based on one of these types of scales, it makes sense why we continue to use these 7 letters.

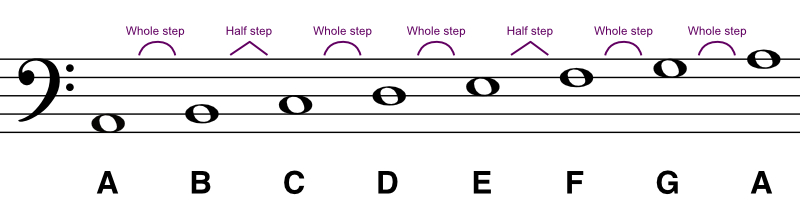

As seen in this image, the 7 notes of a diatonic scale have varying distances (intervals) between them. Between the letters are 5 whole steps (whole tones) and 2 half steps (semitones). A semitone is the smallest interval used in Western music, which means that the distances between B-C and E-F are already the smallest they can be (these letters are as close together as possible).

But a whole step represents two semitones, which means that for every pair of notes separated by a whole step, there is another note halfway between them. Because there are 5 whole tones in the diatonic scale (between the letters A-B, C-D, D-E, F-G, and G-A), there are 5 additional notes.

The 7 natural notes plus these 5 in-between (semitone) notes are the 12 musical notes. These 12 music notes are sometimes called the 12-note scale, 12-tone scale, or Chromatic scale, and they are used by many countries around the world today.

What Are the Names of the 5 In-Between Notes?

Because the first 7 Latin letters are already assigned to the notes of the diatonic scale, the 5 in-between notes are not given their own unique letter names. If they were, they would be out of order with the original 7 letters, something like A-H-B-C-I-D-J-E-F-K-G-L-A. (Imagine how confusing that would be!)

We also cannot rename all 12 notes to be the letter names in order (A-B-C-D-E-F-G-H-I-J-K-L), because this would displace thousands of years of music history, theory, and organization. It would destroy the music staff, forcing us to restructure the way we write and share music. And truthfully, it would be just as confusing, because every scale on which music is based would then have to skip several letters. For example, A Minor (currently A-B-C-D-E-F-G) would then look something like A-C-D-F-H-I-K. (Who wants to try to learn all the different letter combinations for every scale??)

So instead, the 5 in-between notes are given the name of their nearest neighbor PLUS a modifier (sharp or flat sign). This indicates that the note we're referring to is one semitone higher or lower than the given letter. For example, the note between A and B may be called A-sharp (since it's a half step above A) or B-flat (since it's a half step below B). Either name is acceptable; which name they are given depends on musical context and which musical scale is being used at the time.

Why Are Some Letter Notes Farther Apart While Others Are Closer Together?

The 7 natural notes have varying distances between them because of how the diatonic scale is structured. Historically, most scales were built around the most harmonious intervals: the perfect octave, perfect 5th, and perfect 4th. The next most harmonious intervals are the 3rd and 6th. The 2nd and 7th are natural dissonances. Each of these intervals forms a natural stopping point, giving us a total of 7 unique notes. The distances between these notes has to do with harmony, mathematical ratios, and what listeners like to hear.